Christina Rossetti's enigmatic poem encapsulates something of the relationship between the artist and his subject. For her brother, in particular, women she suggests, existed as projections of imagination, fantasy and ideals. Outside the studio, however, Rossetti was very attractive to women who he treated with considerable affection.

By the mid 1850s Rossetti's turbulent relationship with Elizabeth Siddal reached a crisis. She began to take drugs, was frequently ill, and finally the couple parted for many months. In the meantime Rossetti had met Fanny Cornforth at the Royal Surrey Gardens. Model, part time prostitute, voluptuous, lively she had many of the qualities of uninhibited drive that Lizzie lacked. She became Rossetti's model then mistress, and she seems to have given him new sexual pleasures. Nor did she mind giving the same pleasures to Rossetti's close friend W P Boyce. The two set her up in her own flat, and the enjoyment that both of them had with her was celebrated in a picture commissioned by Boyce, Bocca Baciata.

It was, as Rossetti recognised it had a, 'Venetian aspect'. Gone are the ascetic values of the medieval world, and just as Renaissance painters, particularly those in Venice, had celebrated the pleasures they had with courtesans, so Rossetti celebrated the pleasure he had with Fanny.

Rossetti was not alone in shifting painting away from narrative towards the sensuousness of pure pigment, but a picture like Leighton's Pavonia though brilliantly skilful has none of the warmth and allure of Bocca Baciata.

Rossetti's discovery that he enjoyed sharing a woman with another man led to a new orientation in his work, and a burst of creativity. Here he draws Fanny and Boyce in his own studio as Fanny leans affectionately over Boyce. On the wall behind is a portrait of the divorced actress Ruth Herbert, a famous beauty with a harem of lovers.

In Bocca Baciata Fanny is pressed towards the viewer in a moment of meditative intimacy. She allows her courtesan's dress to fall open and make her white flesh available to the viewer. The marigolds, symbols of the sun and creativity blossom in a wall of verdure behind her, and the eponymous mouth that gave so much pleasure is placed centrally in the canvas. The rich oil medium (Rossetti until now had worked mainly in watercolour), links him with his Venetian originals and speaks of a new painterly mode.

Lizzie Siddal returned to Rossetti's life, crushed by illness and drug taking, and more out of duty than desire Rossetti married her. Their married life was brief, but long enough for her to become pregnant, though the female child was still-born. Depressed and isolated, she overdosed on laudanum. Rossetti was overwhelmed with guilt, and placed the manuscript of his poems in her coffin. Some years later in a gesture of remorse he painted Beata Beatrix which, in contrast to his developing Renaissance style, returns to the neo-gothic mode in a picture of Lizzie as Beatrice at the moment of death. Behind stand Dante let by Love.

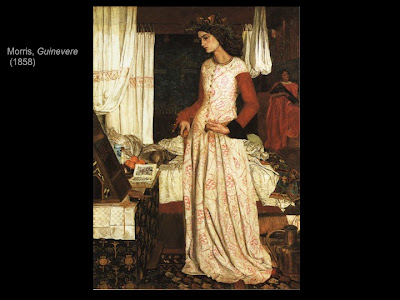

Around 1865 Jane Morris returned from her early married years in Kent to the centre of London and returned, too, to Rossetti's life. His new attraction to her was marked by a series of remarkable photographs taken by the photographer Alfred Parson in Rossetti's garden in Chelsea.

Her dress, loose and dark, though it covers her body also serves to reveal it. In direct contrast to contemporary fashion she wears neither crinoline nor corset.

This fact was noticed by Henry James when he first visited the Morrises in London in 1869. In a famous letter to his sister he suggests that Mrs Morris probably is has no underwear on and he is startled by her dress, her manner and her physiognomy. He saw her as the quintessence of Pre-Raphaelitism, a fact that was reinforced by a portrait of her The Blue Silk Dress that Rossetti had just given her as a present and that hung in their sitting room.

The painting (as the accompanying sonnet suggests) is a gesture of defiance and possession. In another triangular relationship, Rossetti had managed to seduce Jane into temporarily abandoning her children and her husband. The relationship passionate, all consuming and dangerous stimulated Rossetti into some of his most vivid and energetic poems and pictures. James noticed the obsession when he visited Rossetti in his studio.

Urged by all those around him to publish his poems, Rossetti had to recover the manuscript book buried with Lizzie Siddal. In famous, macabre scene in Highgate Cemetery her coffin was brought to the surface. After the book had been fumigated Rossetti transcribed the poems, and with the aid of his brother William Michael and the poet A C Swinburne, edited them along with poems written since Lizzie's death. They were published in 1870.

In 1872 William Buchanan under the pseudonym of Thomas Maitland attacked Rossetti in a famous article 'The Fleshly School of Poetry'. He accused Rossetti of writing a kind of pornography that would infect others across the land. Rossetti was devastated by such public humiliation thinking that it would expose his treatment of Lizzie, his affair with Jane and his betrayal of his friend Morris. He took an overdose of laudanum in the hope of following Lizzie to the grave, and was at first given up for dead.